Attempting new design development system

Shinichi Yamamura, President, Cobo Design Co.,Ltd.

―― Urgent compact car development

The year 1970 was almost upon us, and soon after the completion of the Galant Coupe FTO (hereafter referred to as FTO) design project that I was in charge of, the design project of the Lancer, a compact car in the 1200-1600cc class, which was one rank lower than the Galant, was begun. At the time when the “3C’s” (car, cooler, and color TV) were the new three sacred treasures of Japan’s high economic growth period, the market for compact cars such as the Nissan Sunny and Toyota Corolla was growing rapidly. Against this backdrop, the Colt 1000F and Colt 1100, which appeared in 1966, were struggling at the end of their model life. Consequently, the development of this class was urgent and the development schedule was extremely tight, as was the case with the FTO.

Toyota Collora photo courtesy of Toyota Automobile Museum(left)Colt 1000F(right)

The design studio for the early stages of this project was Studio 3 on the proving ground at Nagoya works, the same location as for the FTO project. The members were Kamisago, myself, Harada who was with us at FTO, modelers Mitsuya and Shiiba, Higashimatsu, “the god of line drawings”, Hasegawa, “the father”, and Sano, as well as energetic new members, such as designers Kashizawa, Tahara and Furukawa, modelers Kiyofuji and Takuzo Ito.

―― New design development system

Discussion in joint work with relevant departments

In order to meet this tight schedule, we made a plan to introduce a web-like development system into the design development process that would allow various processes to proceed simultaneously, similar to the NASA project in the U.S., which was a hot topic at the time. Kamisago and I made a presentation at the general managers’ meeting in charge of the development.

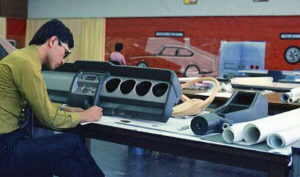

The first method was to introduce NASA’s development system management. To facilitate and speed up the initial basic design, the body design, chassis design, equipment design, engine design (Kyoto Works), and production engineering departments were to work together, and an unprecedented complex project was realized in which each department had its own drawing board in Studio 3. I have fond memories of discussing the layout of the engine and auxiliary equipment with two energetic designers from the Kyoto Works’ engine design department.

Tape drawings in early stage

The second method was a new model-making system. Instead of the conventional clay model, the model for the design review was a workable resin (Polywood) model ordered from an outside vendor, and multiple design models of the front fenders, hood, etc. were changeable in front of the executives. This was done to make the model look as close as possible to the actual car so that the executives could make an accurate judgment. At the same time, the lack of time and budget to produce multiple models was used as an opportunity to instantly change the beautifully finished and painted fenders and hood, just like on a Kabuki stage. This presentation allows the executives to select the best proposal from several designs. This presentation was very effective with an unexpected and delightful “wow” factor. Needless to say, the project was a huge success, with a drastic reduction in schedule and modeling costs. I would also like to add that this new system was made possible with the help of an outside wood form maker, Mitsuya and Shiiba, those who were in charge of planning the difficult model, and Takuzo Ito, who excelled at woodworking and modeling.

―― Promoting role of design

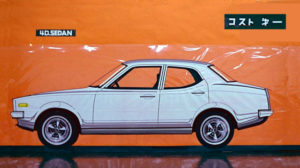

Although the joint project with design, engineering, and production engineering ended only at the initial stage, this joint work in the design studio not only maintained common understanding and accuracy in the preliminary planning stage but also contributed greatly to shortening the schedule in all development stages from the start to the launch. I am convinced that this has been the case. Furthermore, until then, there were unfounded misunderstandings and rumors about the work of the design section, such as that it caused higher costs or that it went out of its way to create shapes difficult to manufacture technically, but by working jointly with other sections, they were able to see how designers were working together to create attractive cars in pursuit of market competitiveness. We deliberately hung the slogan “Cost First” on the wall of our studio for this project to emphasize that we designers are not just thinking about the shape of the car, but about the overall perspective of the car.

Slogan “Cost First” on wall

―― Lancer as the vanguard

In 1970, in the midst of this project, each of Mitsubishi’s car manufacturing plants was separated from Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd. and spun off as a new company, Mitsubishi Motors Corporation. For Mitsubishi Motors Corporation to survive as a car manufacturer, the Lancer, which followed the Galant series, which was popular in the upper class of compact cars, and the FTO, which was to be launched next, was designed to meet the needs of the growing Japanese market, which was expanding in proportion to Japan’s rapid economic growth. This was the knight on the horse of the car’s name, the Lancer.

―― Design for rally

From the very beginning of the Lancer project, a product concept was established with “a compact car that is competitive in rallies”. This was based on the 1967 Colt 1100F’s winning in a class in the Southern Cross Rally. Toyota and Nissan, which had been involved in rallying from early on, saw rallying as an important element of their sales strategy for attracting young people.

This concept was incorporated into the lightweight and torsionally rigid body design, as well as the basic design of the engine and chassis, and we also took a proactive approach to rally-oriented body design. Unlike the flat and sharp body design of the Galant series using stretch-draw press molding, the three-dimensionally curved and taut body design enhances the body rigidity required for rough road driving in rallies. The protruding fenders and the prominent hood, which allowed for the possible future installation of a 2,500cc engine, were also designed to give the impression of big power in a small car.

Clay model in early stage

―― Originality over trends

The basic exterior design is an orthodox notchback style, yet the rear is sharply trimmed to achieve good aerodynamics. This is also to reduce turbulence caused by airflow flowing backward from the rounded rear quarter panel and winding in at the rear end of the body. The trunk opening is wide and extends all the way to the bumper for easy loading and unloading, and is designed to be user-friendly for the families and young people who were the target users. The rear lamps follow the contours of the rear end of the car in a distinctive vertical shape, making the Lancer instantly recognizable. The front area was designed to emphasize the Lancer’s uniqueness and to make the most of the round, dual headlamps, rather than following popular design trends.

Meanwhile, the interior also emphasizes the same rally concept as the exterior. The instrument panel, in particular, was designed in response to strong requests from motorsports teams, with simple, easy-to-read gauges and easy-to-operate switches and levers, in a clear, orthodox style with a circle and square motif. The design was also aimed at making it easy for rallists and general users to customize the car with additional instruments and other equipments.

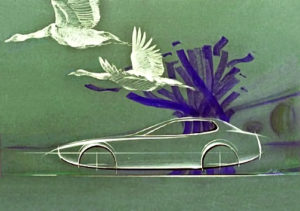

When the design was almost finalized, Kokuhiro Shibuya, a second-year designer, drew a sketch of a “Migrating swans” as a design image for the Lancer. The sketch of the swan on a green illustration board was displayed above the studio, and the body color of the model was decided to be “Siberian White” from this sketch.

|

Final design see-through model painted in Siberian White |

|

―― Celebrating success after launch

After the development was completed, we were very anxious to see whether Lancer’s design, which does not easily follow trends, would be accepted in the market, but I remember feeling relieved that we had done the right thing.

Immediately after its launch in 1973, the rally car, based on the Lancer 1600GSR, was a dominant force in rallies around the world. Following a 1-2-3-4 finish in the Southern Cross Rally that year, in the Safari Rally the following year when Joginder Singh won the championship ahead of his nemesis, the Porsche 911RS, the entire staff celebrated. The image of the “Rally Lancer ” became unshakable and was carried on in the Lancer Turbo and Lancer Evolution that followed.

Lancer 1600 GSR driven by Joginder Singh in the 1974 Safari Rally, Mitsubishi’s first WRC victory.

October 2021