Mitsubishi’s first sports car abandoned

Shinichi Mitsuhashi

Around 1997, after I had retired from Mitsubishi Motors, I was asked by Mitsubishi to compile an internal record of the history of the design department. So, under the title “Mitsubishi Motors Design Trajectory,” I asked the designers who were in charge of notable old models to write down their memories. Although the focus would naturally be on the production models, I thought it would be necessary to write about some of the cars that did not make it to production for various reasons. There are many lessons to be learned from the development of such cars that unfortunately failed, and I thought it was important to leave them behind in history.

Among those cars, there is one that I was first assigned to design as a chief designer, but disappeared like a phantom, and remains strongly in my mind. I would like to trace my memories of this car, based on a story I contributed at the time.

―― Start of sports car project

Ever since the Design Section was established at the Shin-Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Nagoya Works, we had been writing a Studio diary. The members of each studio group took turns writing about the daily events, which sometimes included protests against our superiors and executives and were not meant to be shown to others.

The new Studio diary, dated October 20, 1964, has “SPORTS CAR ○○” (○○ being the code name) written on the red cover, and the first page it says only “Start of sports car project”. That morning, we were called to the room of General Manager Tsubota, who explained to us about the new model to be developed. The first thing he said was, “This is Mitsubishi’s first sports car. This car will use some of the components of the Colt 1000/1500 but will have a new exterior and interior. The rear seats will be a minimal two-plus-two layout, and the styling will feature a sleek image with excellent aerodynamic performance,” he read out the outline of the project and its schedule. The final and more surprising statement was the following: “The chief designer shall be Mitsuhashi. He entrusted this job to me, a young man in my fifth year with the company, who until then had even been acting in a way that defied him.

―― Exploring design proposals

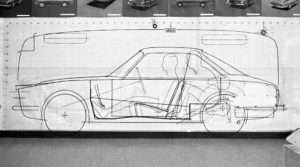

The initial design team consisted of only three members, including myself, but was soon reinforced and we all worked competitively on sketches. The term “sports car” covers a wide range. A variety of designs were developed, from hot to gentle types. We drew three-view sketches to make the proportions easier to perceive.

After that, we moved on to the 1/5th model, and completed three models from proposal A to C with different directions; proposal “A” was the hot fastback design while proposal “C” was the gentlest semi-notch back design, and we secretly hoped that proposal “A” would be selected.

Viewing the models, General Manager Tsubota, who was conservative by nature, said that proposal C was the better choice, as was expected. However, at the upcoming design direction meeting, Executive Director Kubo, the head of the Automotive Division, will be in attendance. He was an aircraft designer during the war, and the “Type 100 Command Reconnaissance” which he designed, was known for its beautiful, sleek design. We believed that since he had pursued such functional beauty, the fastback proposal “A” would surely be selected.

Type 100 command Reconnaissance designed by Kubo

I was shocked. After my presentation, Kubo pointed at proposal “C”. The sleek hot design that we young staff had favored was rejected, and the orthodox and safe proposal “C” was chosen. This was an unexpected result. Tsubota and the rest of the top brass looked relieved. What in the world was going on? I was shocked because I was so confident. “It’s good that it’s been decided, but are you sure this is the way to go?” “The front is too gentle and uninspiring.” “It’s too late. It’s all right now.” “I know, but if you don’t work hard until the end, you haven’t done it” “Shouldn’t we tell our superiors, let us try other proposals that would make things better?” “Then, who is going to propose it and how?” A senior staff member, Ieda, who was standing nearby, said to me. “You’re the chief, Mitsuhashi. You should propose it. Tell Kubo-san directly next time.” I thought I was in trouble, but it was the consensus of everyone, and I gathered my courage and decided to propose again.

Proposal “A”

Proposal “B”

Proposal “C”

―― Re-proposal in opposition to selection

The 1/5 models that were hastily created for the re-proposal were satisfactory, thanks to the strong enthusiasm of everyone involved. The proposal “D”, a fastback, was particularly reminiscent of a Ferrari, while Proposal “E” caught the eye with its boldly cut rear end of the body in the coda tronca style. At the time, our source of information was the Italian magazine “Style Auto,” and we were fascinated by pictures of the latest sports cars, such as the Ferrari 250GT, Alfa Romeo Canguro, and Lamborghini 350GT. Looking back now, however, I feel that we were still immature as designers at that time, just following the trends of others.

Proposal “D”

Proposal “E”

―― Heroes of the Era

Now, let me go a little sideways here. Just before this work began, in May 1964, the Colt 1000 won its class in the 2nd Japanese Grand Prix, and the battle between the Porsche 904 and the Prince Skyline GT became a historical event to be told in the years to come. From this time on, motorsports became widely known in Japan, and sports cars became the heroes of the era.

Against this backdrop, the 1960s was a period in which Japanese automakers launched sports cars in droves: the Datsun Fairlady and the Prince Skyline Sport appeared in 1962, followed by the Honda S600 and S800, the Nissan Silvia, the Toyota Sport 800, the Toyota 2000 GT, the Mazda Cosmo Sport, the Isuzu 117 Coupe, and the Nissan Fairlady Z. Our sports car project was in the midst of such a period.

Colt 1000s at 2nd Japanese Grand Prix

Datsun Fairlady / Toyota Sports 800 / Nissan Silvia

Honda S800 / Mazda Cosmo / Toyota 2000GT

Isuzu 117 Coupe / Nissan Fairlady Z

Photo courtesy of Toyota Automobile Museum

―― Design direction

Back to the story, one day in May 1965, we proposed new proposals to the executive director who came from the Tokyo head office. He looked at my stiff face and smiled, but the result was a resounding no. He only confirmed that the initial design was acceptable. In other words, he wanted to keep it elegant, not aggressive as we insisted. Although all my concerns had not been resolved, I felt refreshed for some reason. ”Mitsuhashi, this is a rather gentle style, but I think it’s as good as it gets.” He understood the designer’s enthusiasm. ”The level is high and the direction of pursuit is correct. However, proposal “C” is still progressive for our company,” He explained the company’s policy, making eye contact with me. I felt closer to Kubo, who had been difficult to approach.

Proposal “C”

Compact sports car layout

―― Hard edged interior design

While the exterior design direction was finalized and proceeding to the finishing stage, the interior design was developed under the leadership of Koya Watabe. The instrument panel design was extremely clear-cut, with the meters and switches arranged on a flat panel and covered by a large, arcing meter hood, creating an atmosphere of functionality like that of an old fighter plane. I was impressed by this hard-edged design, which is unique to Watabe, who thinks logically and scientifically about things.

Interior model(left) Yoya Watabe’s sketch(right)

―― Completion

In June 1965, about eight months after the start of the project, the design was approved for a full-size model named “COLT SPORTS. Toshio Hasegawa, who was in charge of line drawings, was the last person to write in the “Studio Diary,” and he concluded with the following words. “Everyone did a great job. Let’s drink a toast.” We held a small party to thank each other for our hard work and toasted each other loudly. I couldn’t help but imagine the Colt Sport attracting attention at the Tokyo Motor Show and even competing with other sports cars in the Japanese Grand Prix.

Clay model in near-final stage

Wind tunnel test(left) Installation of plate with car name(right)

―― Stunned by sudden cancellation

One day at the end of that year, however, we were suddenly informed that the project had been canceled. Horinouchi, responsible for the project’s development, came to the studio and explained the reason for the cancellation with a somber look on his face. The reason was a change in social conditions. Indeed, that year was said to be the biggest recession after the war. For a while after that, I was in a state of depression. I remember that I became so depressed that I refused to go to work for a while, but this was not recorded in our daily, so I am not certain about that.

In 1966, the year after Colt Sports was abandoned, Mitsubishi entered the 3rd Japanese Grand Prix with the Colt F3A, a formula car with an engine tuned for racing from the Colt 1000. It won the exhibition race over the prestigious Brabham and Lotus. I was deeply moved by the thought that this engine could have been used in the Colt Sport.

Colt F3A

Photo courtesy of Galant GTO Network

―― 30 years later

When I visited the Okazaki studio after my transfer to the head office, I found a picture of the Colt Sport on the desk of a young designer. ”This looks still pretty good today.” He seems to like it quite a bit. “I wonder why they didn’t launch this. If this had been launched, I think it would have enhanced Mitsubishi’s image,” I replied, a little puzzled. “A product like a car, which requires a huge investment, requires a careful decision based on a detailed plan. It is not possible to go ahead with the production just because of its good styling or excellent performance. At that time, too, the recession was cited as the reason for the cancellation of the project, but I believe that the decision was based on an assessment of the company’s capabilities, including profitability and sales capacity. Back then, when I heard that the project was canceled, I annoyed my boss with my complaints and bitterness, but now I’m grateful for my many experiences on this project.” He listened silently with a look on his face that said that was how things go.

―― And now

Looking back, I believe that the Colt Sport was a project initiated by Kubo himself, who was the head of the Automotive Division at the time. This is because he was one of the few people in the huge organization of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries who saw the car not only as a product for business but also as an object for people to love.

January 2023